A D V A N C E D M A T E R I A L S & P R O C E S S E S | N O V E M B E R / D E C E M B E R 2 0 1 5

2 4

components, which he calls fuses, with-

in steel structures to absorb energy

caused by a major event in a way sim-

ilar to how shock absorbers prevent

damage in cars.

“In civil engineering research, the

whole realmof newmaterials is some of

the most important and exciting work

ever experienced in the field, and will

be for many years to come,” says Hajjar.

4

LIGAMENT REPAIR

At Northeastern University’s de-

partment of chemical engineering,

mechanical testing is essential in

developing better materials for liga-

ment repair. In biomedical polymer

research, this typically involves simu-

lating conditions in the human body

such as the real-life movement of ten-

dons and tissues in a wet test environ-

ment. For example, the department

uses a micro-test system to measure

mechanical properties of miniature

samples and is able to measure very

low forces and small displacements.

The system also records microscopic

material behavior while the sample is

subjected to forces such as in charac-

terizing viscoelasticity properties.

In addition to ligament repair re-

search, faculty and students also focus

on hydrogels development, a material

popular in tissue engineering given its

potential to mimic the body. “We use

our test system to pretend we are in-

jecting the hydrogel into bone or oth-

er tissues,” says Tom Webster, chair of

the chemical engineering department.

“Once the hydrogel solidifies, we test

the interface between it and the natural

tissue.”

If the interface is bad, a crack will

begin and failure will occur. If the inter-

face is good, it will withstand a lot of

force. The university is testing applica-

tions including injecting into bone, lig-

aments, and the heart to heal damaged

tissue and rebuild healthy heart tissue.

“The future of mechanical testing is

to tell us how new materials behave,”

says Webster. “The world needs better

materials.”

5

IMPROVED MEDICAL

ADHESIVES

Researchers at the Harvard-MIT

Laboratory of AcceleratedMedical Inno-

vation at Brigham and Women’s Hospi-

tal believe that innovation occurs at the

interface of disciplines. “The constant is

that we focus on solving medical prob-

lems and we constantly test our solu-

tions in multiple models,” says director

Jeffrey Karp. Getting every solution to a

human testing phase as efficiently and

quickly as possible is what gives the lab

its sense of urgency.

The lab is working on how to

reduce injuries to the fragile skin of

premature newborn babies when the

adhesives holding the medical mon-

itoring devices are removed. Lab re-

searchers designed an adhesive with

a middle thin layer of silicone etched

in spider web inspired patterns that

enables quick and painless release. To

conduct proof of concept tests, Karp

used an adhesive testing system for

standard peel and shear tests, and

added an innovative non-machine

approach: Researchers tested the ad-

hesive on origami paper to simulate

fragile skin.

The first priority of testing is to

understand the most critical point of

failure. “If we use mechanical testers

in labs, we can fail fast,” Karp explains.

He adds that testing can help acceler-

ate the iterative process of innovation.

With regard to the lab’s work on devel-

oping adhesive tissue that will attach

to the heart, Karp explains the testing

challenges. “We need to understand

this environment and the extension,

compression, and force that our mate-

rial will be up against. How often will

it be extending? How does the mate-

rial change as it degrades?” he asks.

The liquid adhesive is known as HLAA

(hydrophobic light-activated adhe-

sive), which features a combination

of qualities that enable it to adhere to

a constantly beating—and therefore

moving—heart in the body’s wet envi-

ronment, and to biodegrade during the

healing process.

Other innovations the lab has

developed using its accelerated pro-

cesses include a micro-needle based

adhesive that results in minimal tissue

damage. The needle’s cone-like struc-

ture enables easy insertion into skin

and locks into place as the tip swells

from absorbing water in the body. Re-

searchers in the lab tested the adhe-

sive properties of the micro-needles

and conducted tensile and force pull-

out tests.

~AM&P

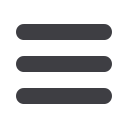

For more information:

Rich Gedney is

CEO of Admet Inc., 51 Morgan Dr., Nor-

wood, MA 02062, 781.769.0850,

sales@ admet.com,

www.admet.com.

TomWebster, chemical engineering de-

partment chair, Northeastern University.

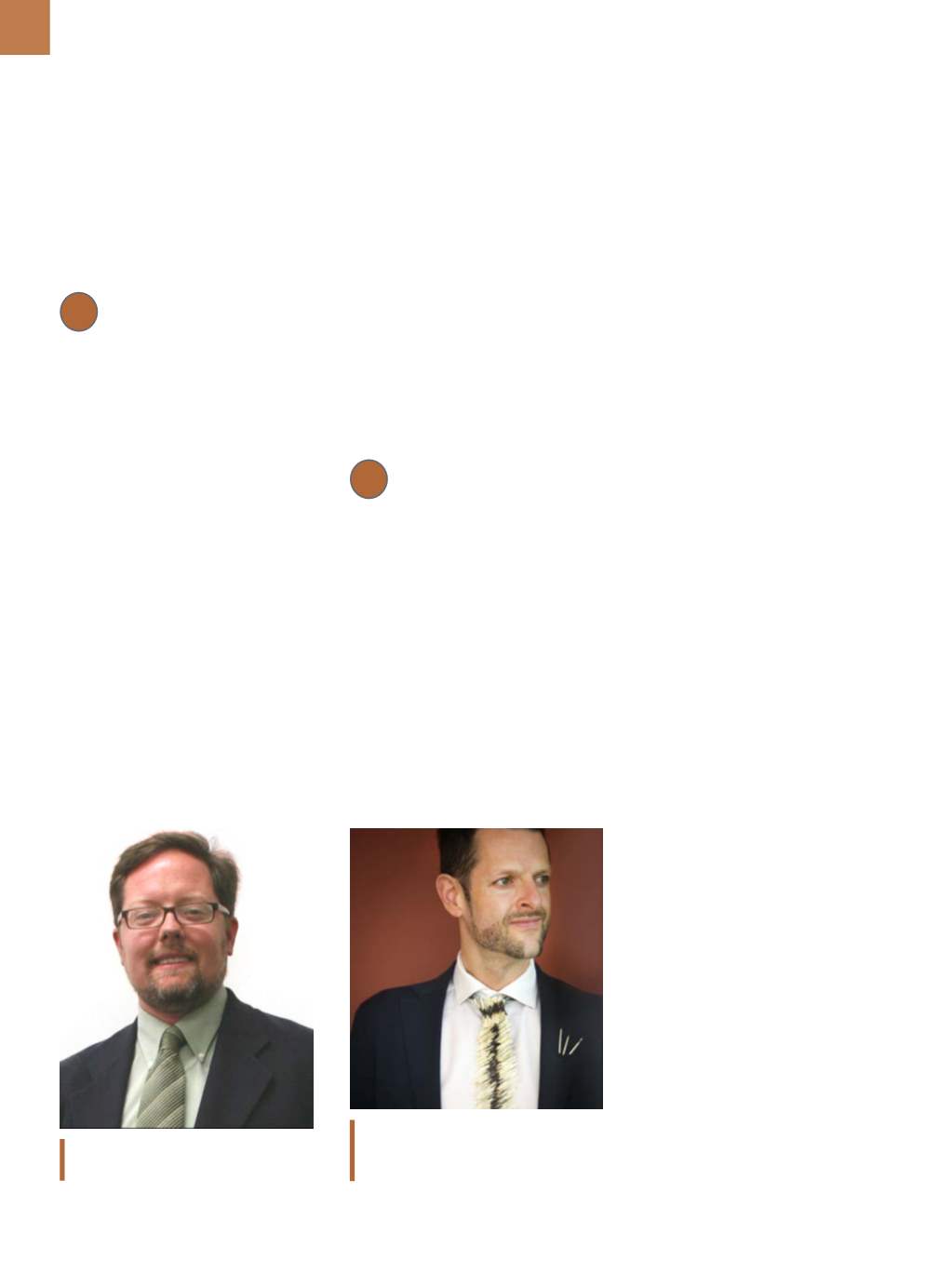

Jeffrey Karp, director, Harvard-MIT Labo-

ratory of Accelerated Medical Innovation

at Brigham and Women’s Hospital.