A D V A N C E D

M A T E R I A L S

&

P R O C E S S E S | J U L Y / A U G U S T

2 0 1 6

1 9

TECHNICAL SPOTLIGHT

BIOCOMPOSITE MATERIALS

FOR ORTHOPEDIC SPORTS

MEDICINE IMPLANTS

The fourth

—

and most recent

—

step in the evolutionary ladder of materials

for orthopedic sports medicine applications involves composites

made of one or more bioabsorbable polymers.

O

ne of the most important aspects

of orthopedic sports medicine is

attaching soft tissues such as ten-

dons and ligaments to bone. This attach-

ment process is facilitated by a wide

variety of implants in the formof anchors,

buttons, pins, staples, and screws.

Mechanical strength and biocompati-

bility are important properties of these

devices and early generations of implants

weremade frommetal alloys suchasNiti-

nol and stainless steel or plastics such as

polyether ether ketone (PEEK). Potential

disadvantages of these materials include

interference with some imaging modali-

ties, metal sensitivity, and difficulty with

device removal

[1]

.

In the 1990s, bioabsorbable

homopolymers such as poly-L-lactic

acid (PLLA) and polyglycolic acid (PGA)

were introduced. Unfortunately, when

used in isolation, the former material

tends to have a very long degradation

rate, while the latter degrades so rap-

idly that cysts or draining sinuses can

form

[2]

. The patient’s conflicting prior-

ities between implant absorption in

a reasonably short time and avoiding

soft tissue irritation require a delicate

balance from designers of new mate-

rials for sports medicine implants.

Polymer degradation naturally occurs

in the human body as these acids are

incorporated in the tricarboxylic acid

cycle (Krebs cycle) and are ultimately

excreted from the body as carbon diox-

ide and water

[3]

.

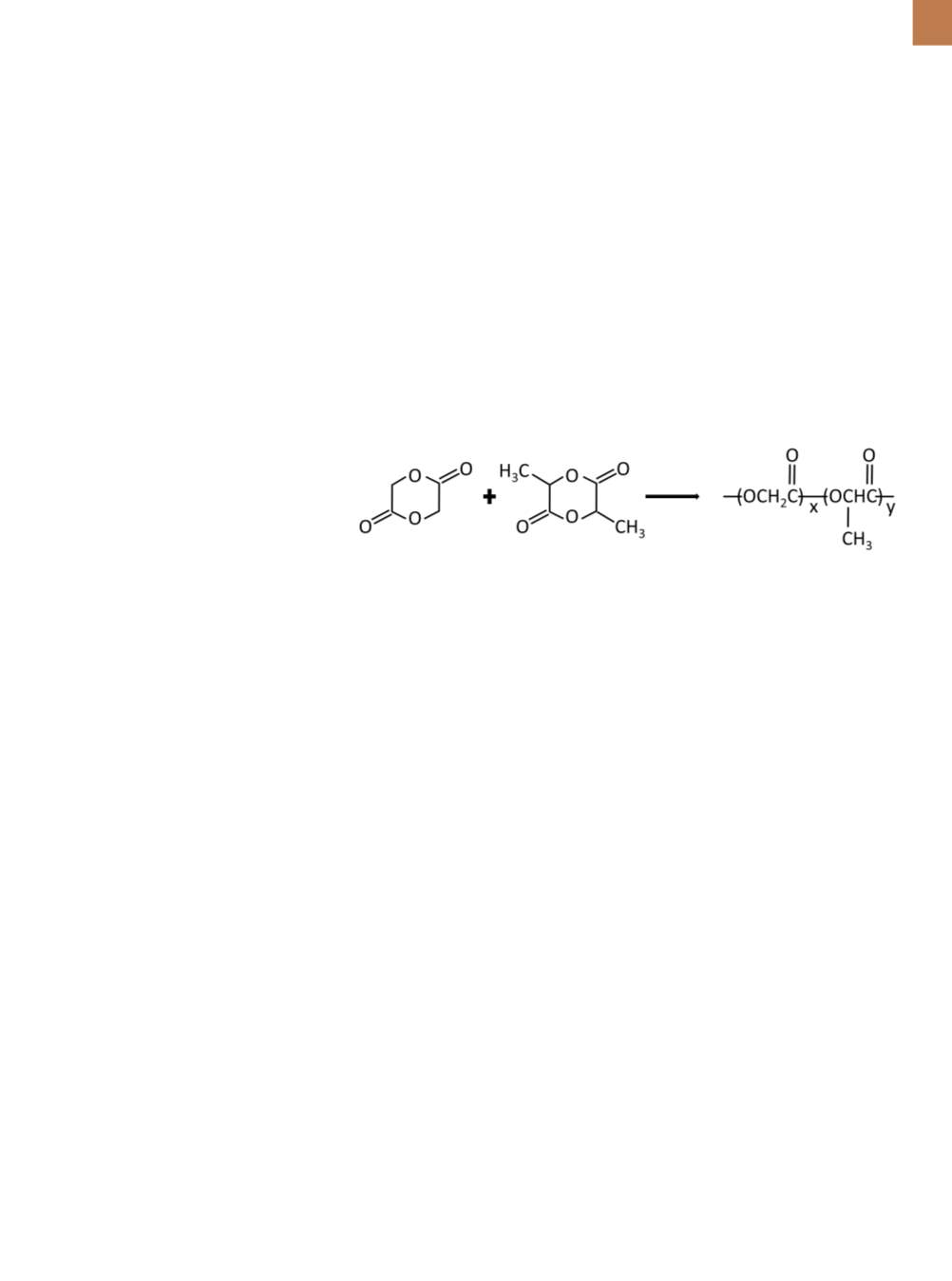

A third generation of implants

uses copolymers of these and other

polymers, as well as stereoisomers of

polylactic acid (PLA) such as combina-

tions of dextro and levo monomers. For

example, L-lactide and glycolide can

be combined to form poly(lactide-co-

glycolide) polymer (PLGA) (Figure 1).

These implants degrade at a sufficiently

fast, but not overly rapid, rate. How-

ever, bioabsorption of the implant does

not typically fill back in with bone, thus

leaving an undesirable area of weak-

ness (i.e., a cavity) in the patient

[4]

.

The fourth—andmost recent—step

in the evolutionary ladder of materials

for orthopedic sports medicine appli-

cations uses composites made of one

or more bioabsorbable polymers with

osteoconductive (bone forming) bioce-

ramics such as

β

-tricalcium phosphate

(

β

-TCP). Extensive preclinical and clini-

cal data exist for one specific formula-

tion comprising 30%

β

-TCP by weight

and 70% PLGA, called Biocryl Rapide

(BR) from DePuy Synthes, Mitek Sports

Medicine, Raynham, Mass. A variety

of implants manufactured from this

material are available including inter-

ference screws for use in anterior cruci-

ate ligament (ACL) reconstructions and

suture anchors for use in both rotator

cuff and labrum repairs in the shoul-

der. All of these surgical procedures are

common in sports medicine.

MANUFACTURING OF

BIOCRYL RAPIDE

Powdered

β

–TCP and PLGA are

dried and then mixed together using

an extrusion machine: The PLGA is

melted and then

β

–TCP is mixed into

the melt using a proprietary micropar-

ticle dispersion process. This technique

ensures homogenous dispersion of the

composite materials (Fig. 2), thereby

reducing the incidence of stress risers

within the implant itself and ensuring

that the osteoconductive

β

-TCP is in

close apposition with the surrounding

bone tissues during the entire absorp-

tion process. The molten composite

exits the machine and is then cut into

pellets approximately 3 mm long. Pel-

lets are later fed into injection molding

machinery to mold specific implants

Fig. 1 —

Chemical structures of L-lactide and glycolide combine to formpoly(lactide-co-

glycolide) polymer (PLGA).