A D V A N C E D

M A T E R I A L S

&

P R O C E S S E S | J U L Y / A U G U S T

2 0 1 6

2 7

Eugene Grace (hand on face) testifying

before Congress in 1955. Grace was

president of Bethlehem Steel from

1916-1945 and chairman of the

board from 1945-1957.

the high production and profits they

had enjoyed for 10 years had come at an

unsustainable cost. While the domestic

steel industry was busy building new

capacity with the open hearth process

that had dominated steelmaking for

over 50 years, new technology was com-

ing onstream in Europe and Japan. First

was the basic oxygen furnace (BOF),

which used oxygen blown through the

heat of molten metal to convert it to

steel. This novel process could convert

cast iron from the blast furnaces to steel

in 45 minutes compared with 8 hours in

the open hearth. The process had been

invented in Austria and was installed in

other countries as new open hearths

were erected at Sparrows Point. One

small U.S. producer, McClouth Steel

Co., had built a 35-ton unit in 1954 and

Jones and Laughlin Steel Co. built sev-

eral in 1959. This would leave the two

biggest steel companies in the U.S.

with new open hearth shops that would

become obsolete in the 1960s.

The second new technology that

was developing overseas was the con-

tinuous casting machine. Molten metal

from the steelmaking furnaces was

ladled into a machine that allowed

solidification as it moved through the

unit and a semifinished product left the

machine. This process eliminated the

old system of casting molten metal into

large ingots that had to be reheated and

reduced to semifinished products either

by forging or in a rolling mill. Bethlehem

Steel would require many years and

billions of dollars to convert its mills to

these new processes.

For more information:

Charles R.

Simcoe can be reached at crsimcoe1@

gmail.com.

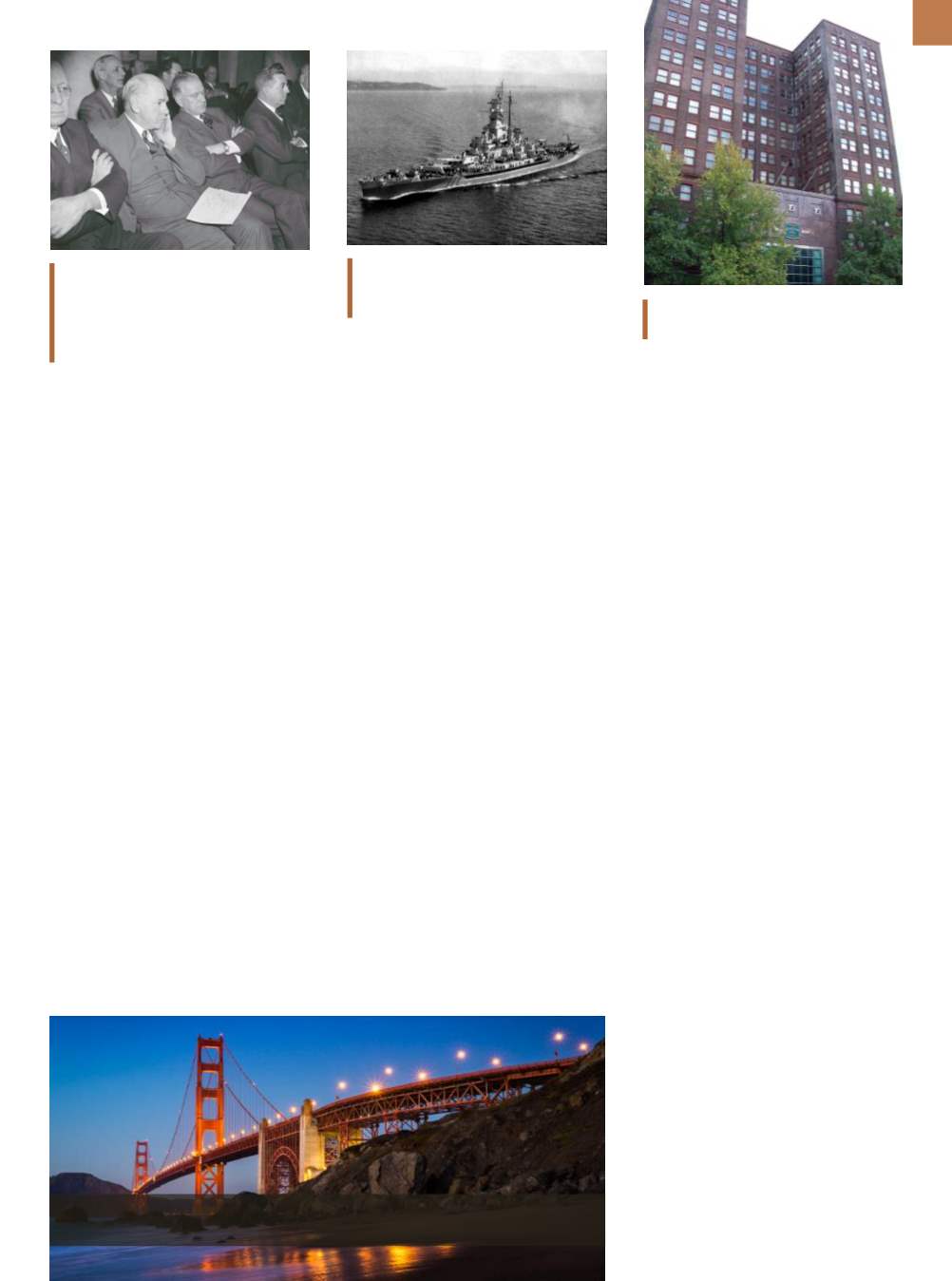

Bethlehem Steel supplied the steel and built the Golden Gate Bridge, which

opened in 1937. Courtesy of Ryan J. Wilmot/Wikimedia Commons.

Bethlehem Steel’s corporate headquar-

ters in Bethlehem, Pa.

The USS Massachusetts (BB-59) was

built at the Bethlehem Fore River

Shipyard during WWII.

in 1933 and beyond, the increased busi-

ness was in lighter flat-rolled products

for the automobile and appliance mar-

kets in the Midwest. Bethlehem only

had one mill that could reach this mar-

ket—the Lackawanna plant where the

company had installed continuous hot

rolling mills for sheet in 1937.

CONTRIBUTIONS

DURING WWII

With the start of WWII in Europe,

Bethlehem received $300 million in

orders from England. (Recall that it was

production for overseas orders during

WWI that allowed Bethlehem to accu-

mulate excessive profits.) This time,

orders went through the War Production

Board instead of J.P. Morgan in London,

therefore limiting profits. During WWII,

Bethlehem’s greatest contribution was

in its shipyards. Shipbuilding employ-

ment increased from 7000 to 182,000,

accounting for 95% of employment

growth for the entire corporation. In

four years, Bethlehem built 1127 ships,

produced 73 million tons of steel, and

furnished the Navy with one-third of its

needs for armor plate and gun forgings.

1950s SEES RENEWED GROWTH

The 1950s were very productive

and profitable for the steel industry, as

demand for steel exceeded that of WWII.

At times, Bethlehem operated at 100%

of capacity with an average of 150,000

employees. Total net income for the

period 1950-1959 was $1.37 billion. With

these reserves, the company added

5 million tons of steel to its annual

capacity, bringing the total to 20 million

tons. In 1954, Bethlehem attempted to

acquire Youngstown Sheet and Tube

to gain additional markets in sheet

products in the Midwest. However, the

merger was prevented by the Justice

Department on grounds that it would

violate the ClaytonAntitrust Act. In 1956,

Bethlehem announced a program to

expand production to 23 million annual

tons. Two million would be at Sparrows

Point, increasing that plant to 8 million

tons with a 10th blast furnace and a new

open hearth shop. When expansion was

complete in 1958, Sparrows Point was

the largest steel mill in the world. All of

this optimism was based on steel con-

sumption continuing well into the next

decade or two.

However, in early 1959 the entire

steel industry failed to understand that