A D V A N C E D M A T E R I A L S & P R O C E S S E S | M A Y 2 0 1 5

2 8

METALLURGY LANE

Metallurgy Lane, authored by ASM life member Charles R. Simcoe, is a continuing series dedicated to the early history of the U.S. met-

als and materials industries along with key milestones and developments.

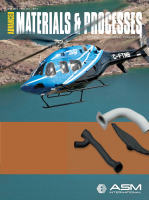

TITANIUM: A METAL FOR THE AEROSPACE AGE — PART III

TITANIUM’S POTENTIAL WAS NOT FULLY REALIZED UNTIL 1956 WHEN METAL PRODUCTION REACHED

5200 TONS AND SPONGE PRODUCTION NEARLY 15,000 TONS.

W

hile the business side of tita-

nium was improving, most of

the alloy product was going

into jet engines. Airframe manufactur-

ers were still grappling with problems

in sheet material, as better alloys were

needed to form parts and improve

strength. More uniform properties were

also needed. Variation in properties

from one supplier to another—or even

within the same shipment—was a cause

for concern. The learning curve for mak-

ing titanium sheet products was more

difficult than expected. In fact, the De-

partment of Defense (DoD) initiated a

$3.5 million project in 1956 to combat a

host of sheet metal problems.

This project, called the DoD Sheet

Rolling Program, was administered by

the National Materials Advisory Board

(NMAB) of the National Academy of Sci-

ences. Representatives from all the ma-

jor airframe manufacturers, jet engine

builders, titanium producers, the armed

forces, and other government agencies

with an interest in titanium assembled

at NMAB headquarters in Washington.

One of the most comprehensive techni-

cal programs ever undertaken in metal-

lurgy was designed by this group to over-

come the problems hindering the rapid

growth of titanium in airframe construc-

tion. Three promising alloys, including

Ti-6Al-4V, were selected for study.

Over several years, this project pro-

duced not only improved alloys and bet-

termaterial quality, but also a deeper ap-

preciation of the reliability of titanium as

an aerospace material. An indirect bene-

fit was the close relationships formed by

individuals within all parts of the indus-

try participating in this common goal.

PEAKS AND VALLEYS

Improved business conditions,

along with rising enthusiasm within

the industry, continued into 1957. First

quarter metal shipments reached 2200

tons, which indicated an annual goal of

perhaps 9000 to 10000 tons. Titanium

was on its way to becoming the aero-

space metal that its promoters had

hoped for. Then an earthquake shook

the aerospace and titanium industries:

Defense Secretary Charles Wilson,

formerly of General Motors Corp., an-

nounced a decision to base the U.S. de-

fense strategy on missiles rather than

manned aircraft. The accompanying

reductions and contract cancellations

rocked the industries, as this major

cutback in aircraft and engine produc-

tion meant a near total collapse of the

titanium market. The most promising

metal of the postwar era—which had

received an estimated $200 million in

government support—was in serious

danger of extinction by the very De-

fense Department that had brought it

into being.

The ramifications were swift and

drastic. Orders were cancelled and by

the fourth quarter of 1957, titanium

shipments skidded to 350 tons. The

price of sponge plunged to $2.25 per lb

as production mounted to 17,000 tons

in addition to competition from 3500

tons of Japanese imports. Metal prod-

uct prices decreased to an average of

$10 per lb. Prices continued to decline

over the next several years to as low as

$1.60 for sponge and $7 for metal.

Many bailed out of the industry.

The Remington Arms Division of DuPont

sold its 50% interest in Rem-Cru to part-

ner Crucible Steel Co., who remained

Pratt & Whitney J58 engine on display at the Evergreen Aviation & Space Museum in Oregon.

Jet engines were the first application to use titanium alloys. Courtesy of

en.wikipedia.org.