ADVANCED MATERIALS & PROCESSES •

APRIL 2014

33

interest in the Frick

Coke Company passed

to the Carnegie Bros.

Company.

After Tom Carnegie’s

death, Andrew enticed

Frick into the steel com-

pany to become the gen-

eral manager. Thus

began the team of

Carnegie and Frick that

would complete the steel

empire that had been

slowly growing during

the past 15 years.

Carnegie’s empire now

included the Edgar

Thomson Steel Works,

Homestead and Duquesne Steel Works, the Frick

Coke Company, the Keystone Bridge Company, and a

variety of small mills, mines, and coke works. It was

the largest steel operation in the country. Within a few

years (by 1892), the output of the newly organized

Carnegie Steel Company would exceed half that of the

entire steel industry of Great Britain, and Andrew

Carnegie owned more than 50% of it.

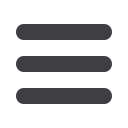

Great strike of 1892

However, the year 1892 would go down in history

for the great strike of the Amalgamated Association

of Iron and Steel Workers at the Homestead Works.

Frick was determined to break the union. To ensure

control of the situation should force be needed, he

arranged for 300 armed guards from the Pinkerton

Agency to stand by ready to help. Frick then rejected

the first proposals submitted by the union and of-

fered terms he knew would be unacceptable. The

workers walked out. When the local authorities were

intimidated by the laborers who were joined by the

whole town of Homestead, Frick sent for his Pinker-

ton force. The 300 guards came down the Mononga-

hela River in two steel barges and attempted to land

at the Homestead plant. Workers lined the riverbank

and the guards were met by a hail of gunfire. The bat-

tle raged all day, but suffered few casualties.

Late in the afternoon, the guards surrendered and

the union leaders promised them safe passage out of

town. However, when they came ashore they were at-

tacked by the entire town. The men, women, and

even children unleashed a fury that killed three of the

guards and injured the rest. Several days later, 8000

troops from the state militia arrived to take over the

plant and return it to management. Labor relations

and worker morale never recovered at Homestead.

Frick’s reputation, as well as that of Carnegie, would

never again ride as high within the industrial and po-

litical scene.

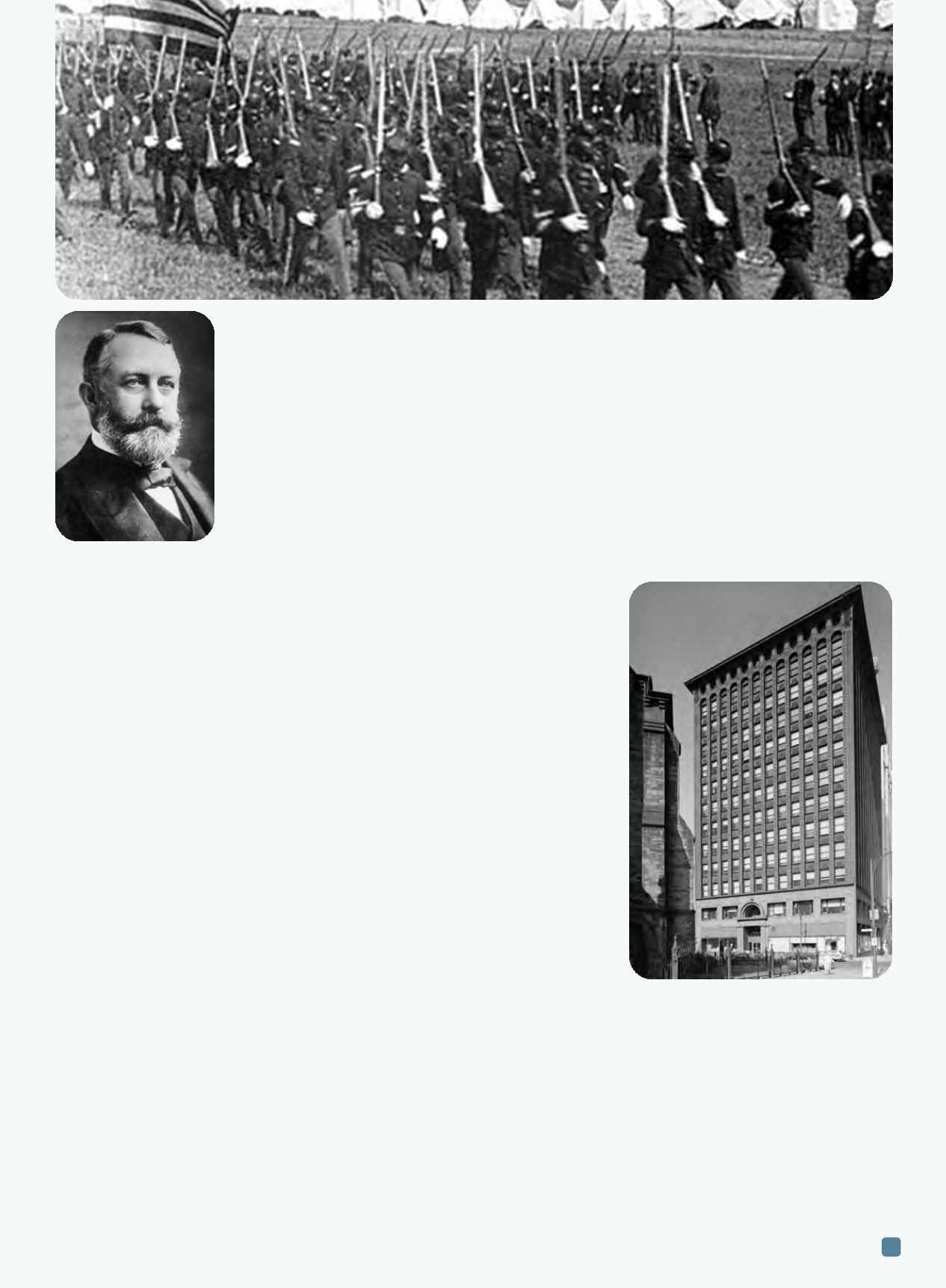

Skyscrapers and steel

move upward and onward

By the 1890s, steel was being used in many new

applications where it permitted breakthroughs in en-

gineering and construction.

One of these was the emerg-

ing world of skyscrapers. The

1890s witnessed such build-

ings going up in Chicago—the

birthplace of these struc-

tures—as well as Saint Louis,

Buffalo, New York City, and

other rapidly growing popula-

tion centers. The cost of steel

had been driven down by

Carnegie and his competitors

to the lowest the world would

ever see. What they all

needed was rapid growth in

their markets. This is what

they got, because they were

standing on the threshold of

the American Technological

Revolution.

It was at this critical junc-

ture in American history that

Andrew Carnegie decided

that he had taken his steel em-

pire about as far as he was

going to go. He was 65 years

old and his lifelong philosophy had been to turn away

from moneymaking for its own sake in order to do

something more useful with his life and fortune. At

Frick’s suggestion, he agreed to entertain offers for

his interest in the steel empire that had taken more

than 25 year to assemble. He sold to J.P. Morgan who

folded his Carnegie Steel Company into a new cor-

poration named United States Steel.

Henry Clay Frick, early

coke entrepreneur and

general manager of the

Carnegie Corp. Courtesy

of Library of Congress/

U.S. public domain.

State militia troops

sent to break the

1892 strike at

Carnegie’s

Homestead Works.

Courtesy of

www.libcom.org.

Architect and “father of skyscrapers” Louis

Sullivan’s Prudential Building, Buffalo, N.Y.

Courtesy of Library of Congress/U.S. public

domain.

For more

information:

Charles R. Simcoe

can be reached at

crsimcoe@yahoo.com.

For more metallurgical

history,

visit

www.metals- history.blogspot.com.