B

efore World War I began, a small

amount of stainless steel cutlery

and tableware was produced in

Sheffield, England. Meanwhile in the

U.S., the first heat of stainless steel was

melted at the Pittsburgh plant of the

Firth-Sterling Steel Co., a subsidiary of

Thomas Firth and Sons, headquartered

in Sheffield. However, the decade from

1910-1920 saw little progress in stain-

less steel production mainly because

throughout World War I, all available

metal was used to make exhaust valves

for aircraft engines in both the U.S. and

England. During the war, one of the ma-

jor stainless producers was Carpenter

Steel Co., a manufacturer of steel for

Liberty aircraft engines.

Most production processes of this

era used the heat-treatable martensitic

grade—13% chromium and 0.30% car-

bon. These general martensitic grades

were covered in the U.S. by patent appli-

cations in March 1915 from both Elwood

Haynes and Harry Brearley. Rather than

fight the conflict in court, Brearley and

Thomas Firth and Sons formed a syn-

dicate named The Stainless Steel Co.

to hold all patents. Haynes agreed to a

30% share in the company and Brearley

and Firth held 40%. Several other U.S.

companies held the remaining 30%.

This solved the problem for ferritic and

martensitic grades of stainless, although

Krupp—in Germany—held patent rights

for the austenitic grades.

Early applications

Throughout the majority of the

1920s, only ferritic and martensitic

stainless steels were made in the U.S.

This was extremely limiting because

during the next few years, the austenit-

ic grades were required for major stain-

less steel applications. The commercial

dilemma was corrected when patents

were exchanged between England and

Germany in 1923, with a royalty paid in

1928 to import or produce austenitic

grades in the U.S.

After the war ended, initial uses for

stainless steel again involved cutlery and

tableware. By 1923, this had expanded

to surgical and dental instruments and

then to containers for nitric acid. New

applications throughout the decade in-

cluded milk handling equipment, surgi-

cal implants, cookware, golf clubs, and

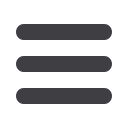

automotive trim. Perhaps the most spec-

tacular was the curtain wall for the upper

seven stories of the brand new Chrysler

Building in New York, including the huge

gargoyles that serve as its architectural

trademark. This building used 48 tons

of austenitic stainless steel, from a total

of 53,000 tons produced in 1929. The in-

dustry was just getting startedwith these

new austenitic stainless offerings, with

steel companies like Allegheny, Ludlum,

Carpenter, Crucible, Lukens, Latrobe,

and others as the major pioneers and

producers.

Meanwhile, in England, W.H. Hat-

field hadmodified the German austenitic

alloy containing 20% chromium plus 7%

nickel to the now familiar 18%chromium

plus 8% nickel (18-8) that became AISI

302 in the U.S. He also added titanium

to combine with the carbon for AISI 321,

greatly improving weldability. 18-8 went

on to become the single most important

alloy in stainless steel because it offers

the ideal combination of corrosion and

acid resistance, formability, and the abil-

ity to be polished to a beautiful finish.

1930s and 1940s

The Great Depression of the 1930s

impacted stainless steel as it did all

metal making. Production decreased

from 58,000 tons in 1929 to 23,000 tons

in 1932. Only a few applications saw

increased stainless steel consumption

during the decade, mainly in the trans-

METALLURGY LANE

STAINLESS STEEL: THE STEEL THAT DOES NOT RUST — PART II

Fromwartime use to cutlery and building facades, the stainless steel industry

began to experience dynamic growth from the 1920s on, especially following WWII.

etallurgy Lane, authored by ASM life member Charles R. Simcoe, is a yearlong series dedicated to the early history of the U.S. metals

and materials industries along with key milestones and developments.

The top seven stories of the Chrysler

Building are covered with austenitic

stainless steel. Courtesy of Petri Krohn and

Leena Hietanen.

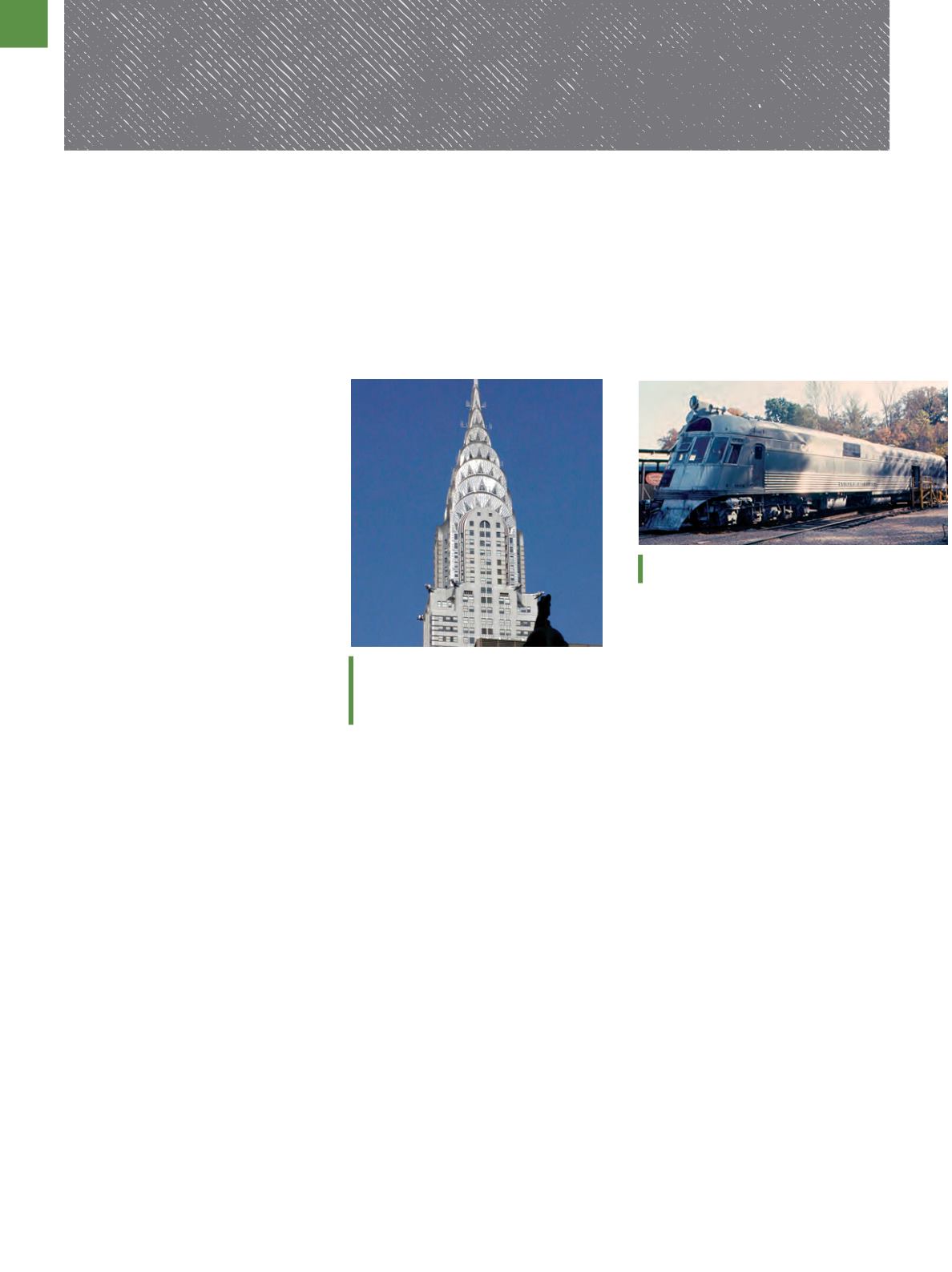

Burlington Zephyr stainless steel passenger

train, circa 1935. Courtesy of Roger Wollstadt.

A D V A N C E D M A T E R I A L S & P R O C E S S E S | F E B R U A R Y 2 0 1 5

3 2